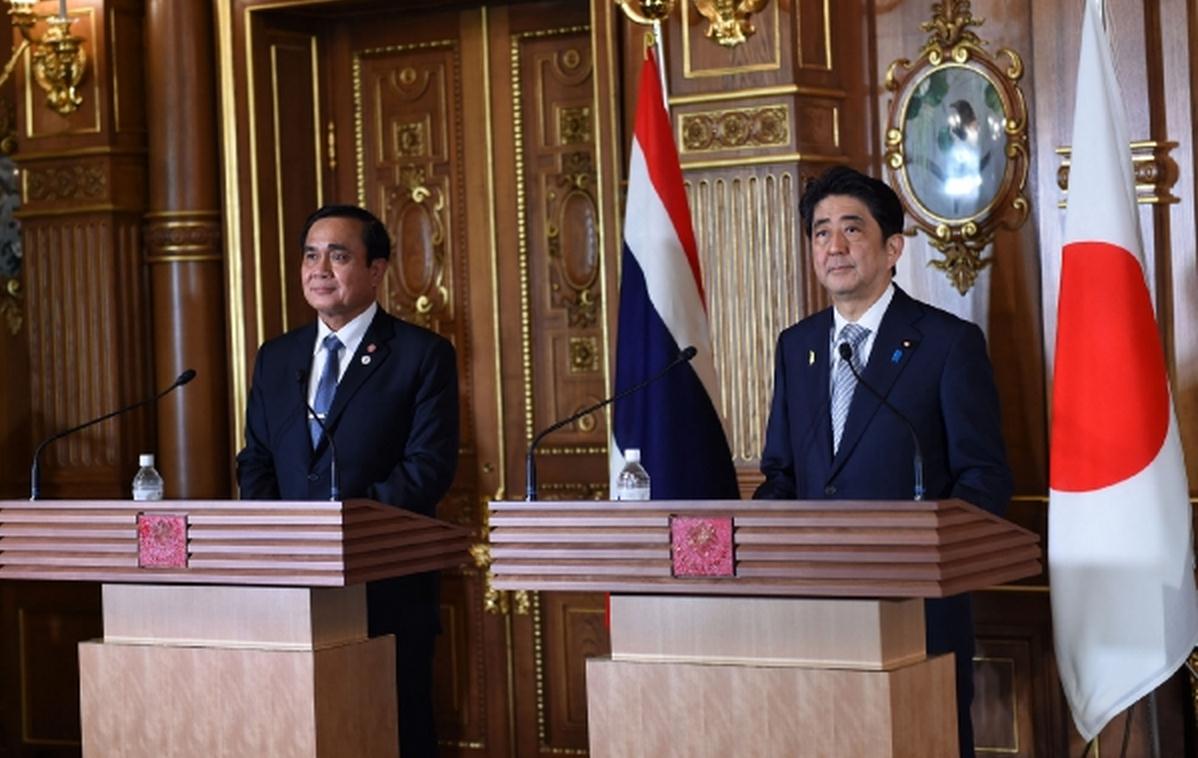

Thailand’s deal with Myanmar – and, importantly, Japan – to develop Dawei, long-expected but now part of a formal agreement between the three countries after the July 4 Mekong-Japan Summit, is an ideal complement to Thailand’s ambitious plans for a network of special economic zones.

Japan’s involvement in the Dawei project, coming only after much foot-dragging, may be in response to increased investment by China in the region. “[The governments of Japan, Myanmar and Thailand recognize] the importance of the three countries in the comprehensive development of Dawei Special Economic Zone project to promote integrated economic development and enhance connectivity in and around Mekong subregion,” says a memorandum of intent signed in Tokyo.

Japan’s involvement in the Dawei project, coming only after much foot-dragging, may be in response to increased investment by China in the region. “[The governments of Japan, Myanmar and Thailand recognize] the importance of the three countries in the comprehensive development of Dawei Special Economic Zone project to promote integrated economic development and enhance connectivity in and around Mekong subregion,” says a memorandum of intent signed in Tokyo.

The Dawei project has been in the works since 2008, and now includes construction of an industrial park with a deep-water port, blast furnaces, oil refineries and other facilities. Japan has agreed to invest ¥750 billion (US$6.07 billion) in the region over the next three years.

Though the Dawei project is in neighbouring Myanmar, Thailand has its own ambitious plans for to develop SEZs within its borders designed to facilitate trade and, longer-term, to build up the country’s industrial base.

“The government has made some significant progress in the setting up of special economic zones. I would like to inform you that all of the six special economic zones have seen much development,” Thailand’s prime minister General Prayut Chan-o-cha said recently. “Over the past year, we were able to build connectivity, transportation routes, customs checkpoints, etc.”

Rather confusingly, the six SEZs are in five provinces: Mae Sot, on the border with Myanmar, Sakaeo, and Trat near Cambodia, Mukdahan on the Laos border and Songkhla in southern Thailand near Malaysia.

The SEZs are definitely not free zones: cheaper migrant labour is neither allowed nor encouraged. “Importantly, I would like the workers within these special economic zones to be made up of locals of nearby provinces,” Prayut said. “This will lend towards the development of local communities.”

Six more locations are scheduled to be developed next year, Prayut added. The government plans for seven SEZs in another five border provinces: Chiang Rai, Kanchanaburi, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom and Narathiwat.

Thailand’s approach to SEZs is all very different to the approach taken by China, which sees its SEZs as very international. The Thai government sees them as local and regional, emphasizing border and intra-ASEAN trade.

Or as Prayut put it: “The government is supporting developments in and outside special economic zones, as well as developments in provinces with potential in border trade and in intra-ASEAN trade.”

The government’s support is very locally-based, but this makes the point. Examples of this include the Mae Sot SEZ, which is seeing the building of a road to bypass the city of the same name along with a second bridge over the Moei River; a highway to nearby Tak (Highway No. 105) and the expansion of the Mae Sot airport.

“The special economic zone for Padang Besar and Sadao border points in Songkhla is seeing the construction of the Hat Yai-Malaysian border motorway, construction of the second deep sea port for Songkhla, and renovation of railways between Hat Yai terminal and Su-ngai Kolok and between Thung Song terminal, Hat Yai and Padang Besar,” Prayut said.

While these projects and others are being worked on incrementally, on an as-funds-allow basis, the government is supporting the ecosystem which will surround such facilities, and again the hand of General Prayut is there. A recent Thailand Board of Investment meeting he chaired targeted 13 industries with an incentive package if they locate in one of the SEZs. The Thai Board of Investment, which operates under the Prime Minister’s Office, is the country’s principal government agency for encouraging investment.

The 13 targeted industries include agro-industry and fisheries, logistics, industrial zones or industrial estates businesses and, rather curiously, those supporting tourism.

On the manufacturing side, ceramic products, textiles, clothes and leather, furniture, gems and jewellery, medical devices, cars and car parts, electronics and electrical appliances, and plastics are all welcome. Investors do not, however, have total freedom to choose their industry, as eligible activities will differ “according to the respective potential, limitations, and needs in the zone,” the Board of Investment said on its website.

Qualified projects will receive the maximum incentives which include an eight-year corporate tax exemption and an additional five-year halving of corporate income tax, the BOI added. Businesses not listed above will also qualify for additional incentives if they locate in a SEZ.

Important though tax and other financial incentives may be, what is making the SEZ more attractive is that they are enhancing the building of other infrastructure. Most recently is the news of the development of Dawei, which was much trumpeted over the first weekend of July. Likely to be built first to connect the Myanmar port with Thailand is a 138 km road from Dawei to Kanchanaburi, where one of the next round of SEZs is expected to be placed. And there is more. Lots more.

The deal on Dawei was signed at the Japan-Mekong Summit, which also saw the passing of the New Tokyo Strategy 2015 for Mekong-Japan Cooperation for the coming three years.

One of its key pillars, according to a statement on Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, is strengthening connectivity, including development of the East-West Economic Corridor and the Southern Economic Corridor as well as onward to India and the development of maritime and air links. Changes are coming, none more so than in places located in those two corridors and also the home of an SEZs.

Kanchanaburi will be part of Dawei, which is the mouth of the Southern Economic Corridor, which goes to Sakeo in eastern Thailand before going onto Cambodia. More potent still is the East-West Economic Corridor which, in Thailand, has Mae Sot at its western end and Mukdahan on its eastern.

These SEZs, while they might be starting small, are strategically well-placed to ride Thailand’s – and the region’s – development, if it happens as currently planned.

By Michael Mackey

Southeast Asia Correspondent | Bangkok